Friends,

Many recent conversations have centered on the potential risks involved with investing in Treasury bonds. Aspiring investors, who are just beginning to understand the mechanisms of Treasury Bonds, quite rightfully raise queries such as, "What happens if the government defaults and refuses to repay? or what happens if the Government in power changes", often drawing parallels with countries like Zambia, Egypt, and Ghana that have issued warnings about potential defaults on their Euro Bonds.

In this article, we will discuss the various factors that could trigger the risk of the Government of Uganda defaulting on its local treasury bond obligations. These factors are particularly relevant in the Ugandan context and should guide your decision-making process when investing in treasury bonds.

The Political question and potential Instability:

(I’m discussing this point as an Investor in Government Securities, not my political views).

This is the most significant risk for bond investors in Uganda, especially as the political transition plan unfolds. As an investor, you need to consider the current political environment and the projected transition to a new president in the medium term of eight years. How stable will Uganda be?

President Museveni and General Muhoozi meeting some key ministers recently

If you assess that the transition will be smooth (Regardless of political preferences, all possible indications suggest that President Museveni will most likely transition his political influence and power to his son, General Muhoozi, by potentially 2030/2031. This appears to be a well-coordinated transition of power, as evidenced by General Muhoozi's military transition to the position of Chief of Defence Forces (CDF) of the Uganda People's Defence Forces (UPDF), then by all means treasury bond investments will be safe from default as this transition will ensure continuity especially in the technical arm that manages the Country’s Treasury.

The unlikely scenario for Ugandan context

However, if your assessment includes a more than likelihood of an unstable political transition either through a remote likely option of political instability like significant sustained demonstrations by civilians, Army topping the government which would lead to suspension of democratic systems and suspension of systems in the whole country and a potential polarization of the country (what Niger has just recently gone through), the risk of default increases to heightened levels, particularly if the country's economy comes to a standstill, squeezing the country's liquidity and leading to the suspension of payments to bondholders.

For any Bond Holders, you want to pray Uganda avoids this scenario in the long term and then you might be good to go.

2016 election demonstrations in Uganda

What percentage of likelihood would you give this scenario happening in Uganda? especially in the medium to long term view? and this would be considered in your bond investments but also factor in the below.

But what would happen if this scenario happens?

case in point is Uganda’s 1981 and what happened to treasury bills held then or recent Niger’s coup impact to its local bonds

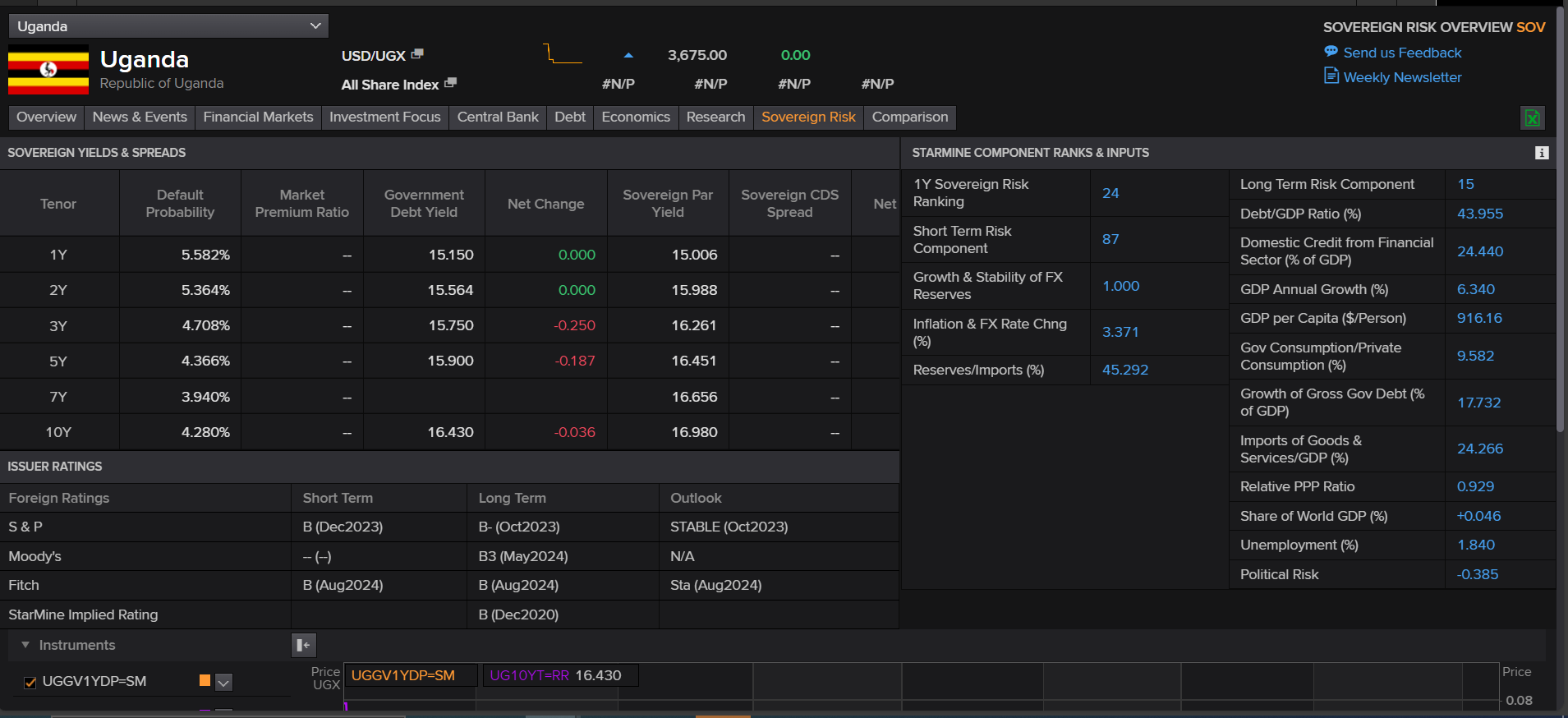

Even in such extreme measures, the likely option would be the suspension can be temporary, lasting about three months, or prolonged for up to 12 months, but eventually, bond obligations are restructured and resumed. This risk is a significant factor in Uganda's B3 rating by Moody's, which we will discuss later.

The leading faces of Opposition in Uganda, Hon Kyagulanyi and Rtd Col Kizza Besigye

On the other hand, if Uganda were to undergo a more democratic transition through an election where the ruling NRM government is defeated by an opposition politician, the risk of default would be mitigated. Such a transition would strengthen trust in the country's systems, potentially leading to a significant increase in foreign direct investment (FDI). This economic boost would enable the new government to honor all bond obligations without fail, as they establish their authority and governance.

Foreign Exchange Reserve Adequacy:

Uganda's trade with the global market continues to be a significant concern for bond investors, but there is some good news on the horizon. With the planned oil revenue projected to start flowing in 2026/2027, as per the Ministry of Finance, bondholders can expect to be paid for the longest time possible as the country expands its foreign revenue base. This will support the growing efforts by Uganda’s biggest earners currently that is Gold and Coffee which are bringing close to $2 billion per year with a potential increase in coming year.

According to the Petroleum Authority of Uganda, the country is estimated to earn over $2.8 billion per year (more than 10% of the current national budget) as direct revenue from oil-related activities, with an estimated $70 billion over the lifetime of the oil project. This figure does not include indirect incomes such as taxes and the economic boost that would increase the government's revenue base.

Oil will be a game changer for Uganda, provided that the oil wealth is managed prudently by trusted authorities and its starts flowing soon.

As an investor in the country's securities, you would want the country's oil projects to succeed fully, as they are crucial for the country's growth in the medium to long term. The government will use some of these borrowings to repay and refinance the current domestic borrowing.

High Refinancing Costs:

This risk arises if domestic banks, which lend the majority to the government, struggle to absorb new government debt, leading to higher borrowing costs. Currently, for every auction, the submitted bid amount for short and long-term bonds exceeds what the government tenders, indicating a low probability of this risk materializing.

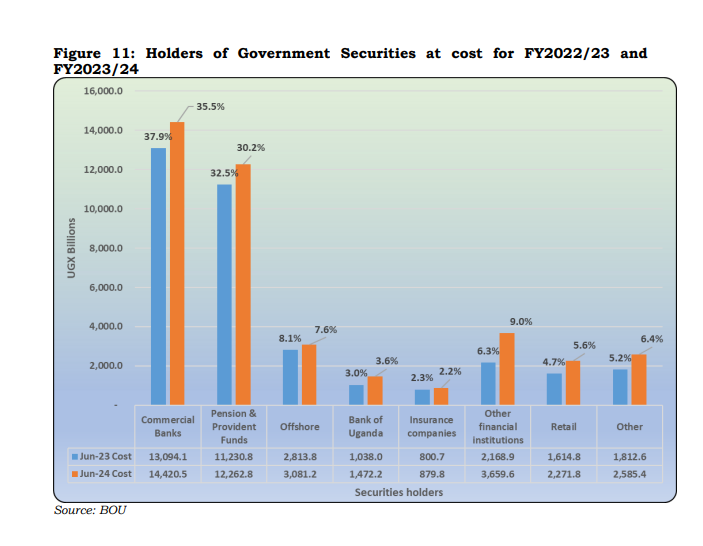

From the graph below, it is evident that commercial banks, pension and provident funds, and other financial institutions collectively own close to 75% of the total government bonds and bills.

As long as institutional investors trust the government and can refinance it beyond its needs through rollovers of short-term debt into long-term debt, the probability of default is minimized, and bond investors will always be paid. All current efforts indicate this is the pathway.

This should serve as a form of assurance for retail investors. If you find it challenging to assess the risk, consider following the actions of major players such as banks, pension entities, and insurance companies. By studying their moves and taking similar actions, there is a higher likelihood that you will be secure in the long run.

Macro-Economic Stability:

The country's macro-economic outlook remains strong, with a projected growth rate of 6%-7% in the medium term, expected to jump to double digits when oil revenues start coming in.

The exchange rate of the Ugandan Shilling (UGX) to major currencies, especially the USD, has been relatively stable over a long period, with the USD crossing the UGX 3,000 mark in 2014 and not yet crossing the UGX 4,000 mark 11 years later.

Inflation has also been maintained at expected levels of 4%-5%, with projected increases around 2026/2027 due to political factors, as has always been the case in Uganda during election periods. As long as the government can continue to raise revenue, especially through the expansion of the tax base, the probability of defaulting on treasury bonds is limited and unlikely to materialize even during challenging macro-economic times. By many measures, the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA) has continued to expand its tax revenue base with little compromise, providing good assurance to bond investors that their investments in the government will be paid off.

Graph below showing the Probility of default of Uganda’s Bonds and bills.

This leads to an important final question; can the Government of Uganda also default on its Treasury bonds in normal circumstances beyond stated above and what lessons do we learn from other countries?

Just like any other form of borrowing, bonds also carry a risk of default. However, there are various types of bonds and each carries different risks. The countries mentioned earlier, along with several other African nations, issued what are known as Euro Bonds in the early 2010s. Euro Bonds are foreign-denominated bonds, primarily in Dollars, issued to western international investors and traded on the international market. These Euro Bonds are quite different from the traditional domestic Treasury Bonds issued in the local currency and traded within the issuing country.

African Countries with Euro Dollar Bonds. Photo by Gregory Smith

Uganda is not on the list above.

Uganda has not yet issued any Euro Bonds; all its borrowings are either domestically through Treasury Bonds or internationally from countries like China and organizations like the European Union, World Bank, and IMF. Therefore, in Uganda, the only bonds prevalent in the bond market are the locally traded Treasury Bonds.

Uganda’s Treasury Bonds

Treasury Bonds are debt instruments by which the Government borrows from the local public in the Ugandan currency. Countries worldwide issue Treasury Bonds as both a monetary and fiscal policy instrument. In Uganda, these bonds are traded either through the primary auction market where they are bought directly from the Bank of Uganda or the secondary market, which involves buying from commercial banks or individual investors.

Ugandan Treasury Bonds have tenures ranging from 2 to 20 years, unlike in developed countries where there are bonds with tenures of even 50 years.

Several differences between Euro Bonds and traditional Domestic Treasury Bonds come with varying risks. The Euro Bonds are issued in dollars, traded internationally, and all repayments are made in dollars. This foreign exchange risk is high for African countries since we barely generate enough foreign exchange earnings needed to repay these bonds, considering we are net importers. In contrast, traditional Treasury Bonds are issued in the local currency that the issuing government can control—governments can print more of their local currency to repay maturing bonds, an option not available with dollar denominated bonds.

Do Governments honor Long-term Bonds after changes in Government or because of any economic challenge? Undeniably, yes! Failing to honor domestic bond obligations would drastically harm Uganda. Major bondholders, such as NSSF and all major banks, have invested heavily in Treasury Bonds. Neglecting these obligations will lead these institutions to fail, bringing down the entire financial economy. As of October 2022, the pension and banking sectors together hold over 70% of the total outstanding debt. Any government default would lead to these robust financial institutions not meeting their obligations and going bankrupt, a situation that neither the Bank of Uganda or the Government would tolerate. Because of these deep ties to the country's financial system, Domestic Treasury Bonds are considered the safest investments.

Euro Bonds, held mostly by international investors, do not enjoy the same protections. Although a default may not immediately impact the country's local financial system, it could make future borrowing challenging.

Lastly, the question of Time value of money and inflation, like all investments, the returns on bonds are impacted by inflation. Uganda's inflation rate hovers around 5-7 percent over the past 10 years, while the return on bonds is nearly 14% for the least expensive bonds. Despite inflation, the returns are still higher. However, the principle of the time value of money implying that money today is worth more than tomorrow, applies even in this case, affecting all types of investments, including real estate.

A very deep and informative analysis. Well appreciated.